SAIGYO HOSHI, ‘Monk Saigyo’, ranks among the greatest of Japanese poets. Born an artistocrat in Heian-kyo, presentday Kyoto, Sato Norikiyo was the scion of a military family who became an attendant to the emperor Toba. He lived almost 1,000 years ago during the late Heian era (898-1185), writing poetry that reflected the courtly taste of the time.

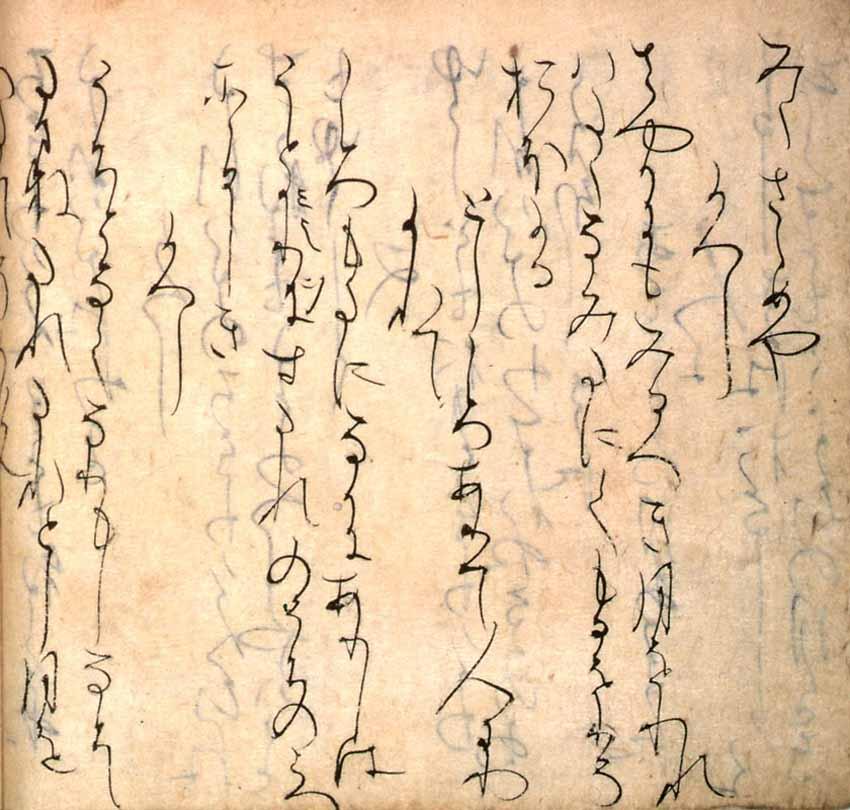

It is not known why he was ordained as a monk at the age of 22, taking the name Saigyo, ‘Western Journey’, in honour of the Amida Buddha of the western paradise then popular in Japan. Saigyo was inspired by all that he saw around him. His poetry was written with a natural vigour surfacing in delicate, threadlike calligraphy whose elegance betrays his pedigree as someone from the literati. ‘The spring wind scattering blossoms, I saw it in a dream, But when I awoke, The sound was still rustling in my chest’ … Saigyo (1118-1190)

Introduction of the Kana Script in Japan

Heian-Style Poetry

In Japan, the veneration of Heian-style poetry remains undiminished today. Kana calligraphy is still considered one of its purest forms of expression. The execution of brushwork conveyed the experience of writing and also revealed the writer’s station in life. One of its most distinguished exponents was Saigyo, said to be unrivalled, very few of whose works are extant today. Celebrating monk Saigyo’s life and work is Kana Calligraphy of Saigyo, an unique undertaking at the Idemitsu Museum of Arts in Tokyo.

Since its inception, the Idemitsu’s renowned collection has grown to represent the art history of Japan in all its manifold aspects. The museum continues to build on the quality of its holding, to include the development of Japanese aesthetics. Indeed the basis for the exhibition is the Idemitsu’s fabled Nakatsukasa-shu, a 10th-century poem anthology by the Lady Nakatsukasa, attributed to monk Saigyo and an Important Cultural Property. Assembled around it are 72 works of calligraphy including 60 acknowledged to be in Saigyo’s hand.

They have been collected from kohitsu, a generic term for ‘old scripts’ in handscrolls, manuscripts and album leaves as well as gire, detached segments, containing verse in full. Among them are National Treasures, ‘those cultural properties … which are of especial high value from the viewpoint of world culture and which are matchless treasures of the nation’.

Poem Anthologies

Important Cultural Properties dating from the 12th century include valuable poem anthologies preserved as family heirlooms from Heian times. Some are gathered from the prestigious Shigure-tei Bunko Library of Kyoto, itself an Important Cultural Property. As a bonus, the calligraphic works are supported by select handscroll paintings from the Idemitsu, depicting Saigyo’s life. On special loan is an exquisite work from the Sannomaru Shozo-kan, the Imperial Household Agency’s museum in the Tokyo Imperial Palace, opened after the Showa emperor, Hirohito’s (r.1926-1989) demise in 1993.

Although early Heian Japan drew substantially from the culture of the high Tang (618-906), a major departure came with the severing of diplomatic relations in 894. Continental influences were regarded only as a resource in the next three centuries, a period of deep cultural introspection during which an indigenous Japanese culture evolved. Nowhere was this more pronounced than in poetry where new criteria were advanced in the writing and composition of poems. In China, this activity was the preserve of the Confucian scholar-gentleman who gave out ethical messages as poet. In Japan, Chinese cultural input was adapted to meet the demands of feudal aristocrats who saw poetry as an end in itself.

Cloistered Nature of Heian Life

The cloistered nature of Heian life spawned new literary forms taking inspiration from court and temple. Women were particularly prolific writers and poets. Life at court has been described by the Lady Murasaki Shikibu in the Genji Monogatari, Tale of Genji, written between 1008 and 1020, and possibly the earliest novel in the world. A spiritual kinship with nature pervaded the sentiments of Heian-kyo court poets.

The preoccupation with the changing seasons, the first snowfall and the blossoming of flowers were all captured in verse. Poetry was an expression of the human condition, narrated against the backdrop of nature as a tale, or seemingly unending tales. A leading female poet was the Lady Nakatsukasa (c.912-c.991), whose anthology of poems, the Nakatsukasa-shu, was often cited in her honour.

On show is a revered 12th-century copy featuring monk Saigyo’s calligraphy, and considered his most authentic work. It appears as a long poetic exchange between the Lady and a loved one, where changing motifs evoking the different seasons, such as the moon and the rain, are given much emphasis.

When Fujiwara no Michinaga became regent, half a century after Japan relinquished ties with Tang China, the composing of poems was a serious courtly pastime. Talented calligraphers were commissioned to write them. The compiling of poem anthologies was jealously guarded by Heian nobility as ‘family treasures’, to be passed down from one generation to the next.

Patronage During the Late Heian Period

The tradition was nourished by the enlightened patronage of the late Heian, also known as the Fujiwara period for good reason. Mighty aristocrats who had risen from the Nakatomi clan in the mid-7th century, the Fujiwara dominated court and country by the 10th. Its elders served as kampaku, the highest ministers, and as sessho, regents, whose monopoly on power was achieved via their female offspring. By supplying their daughters as consorts to the imperial line and even to child emperors, the Fujiwara ensured their hold on the throne went unchallenged.

The Fujiwaras themselves also produced poets. The sixth son of Michinaga, Nagaie, initiated the Mikohidari lineage which had workshops specialising in poem anthologies. Nagaie’s poet descendants included Fujiwara no Toshitada (1073?-1123) whose son, Toshinari (Shunzei, 1114-1204) and grandson, Sadaie (Teika, 1162-1241), being Saigyo’s contemporaries, commissioned the monk to write for them.

An important sample, the Ko-jikishi or Toshitada-shu-gire, ‘Detached segment of Fujiwara no Toshitada’s Poem Anthology’ reads: ‘At the poetry gathering held in my house, Poems centred on the subject of orange flowers, In May, although where the tree of orange flowers stands is not known, We can tell easily, As its fragrance has already reached my house, Blown by the wind’.

Mikohidari Established as Leading Poetic Lineage

The Mikohidari were established as the leading poetic lineage during the succeeding Kamakura period (1185-1333). They were synonymous with poetry, as the Senno Rikyo family were linked in the 16th century, with the tea ceremony. Thereafter the lineage split into three, two of which fizzled out, and only the Reizei line survives today. Heirs to Heian-style poetry ritual, the Reizei family still live in Kyoto.

Since the city was spared bombing during the war, their seat, the Kami-Reizei-ke Jutaku built in 1790 in the Kamigyo ward, is the one noble abode left to those of Mikohidari descent. It has been designated an Important Cultural Property and houses the Shigure-tei Bunko Library, where all existing documents about poetry and court customs inherited by the Reizei are scrupulously kept.

The poem anthologies seldom leave Kyoto. Indeed it is rare to have exceptional sets dated to the 1100’s from the Reizei library, displayed together for the first time. One, the Sotan-shu, ‘Anthology of Poet Sotan’, an acronym of 10th century poet Sone Yoshitada, has a segment with a wintry theme copied by Saigyo: ‘The smoke is gone, There is no sign of anyone living in this small house, But to this house the winter has come, Just like to the others …’

Identifying the Author of a Script

In Japan, a small paper cartouche plays a large part in identifying the author of a script. It is normally attached to the edge of an album or scroll after it is written, where the assumed author is named. An exquisite poem composed and penned by Saigyo himself is a National Treasure from the Kyoto National Museum.

The Ippongyo Wakakaishi, ‘One Chapter from the Sutra’, in waka form, says: ‘If not in two ways, If not in three ways of Buddha’s law of salvation, Sprinkling over like the rain, The five ways of nourishment are the most beneficial, Had I known how deep or shallow this sea of salvation is, I would have gone over safely to the other side’.

Monk Saigyo’s poem was inspired by one of the Lotus Sutra’s 28 chapters whose scriptures, studied and copied at court, taught that ‘All sentient beings are Bodhisattvas, and all can become Buddhas’. Dai-mitsu, Tendai Esoteric Buddhism as practised during the Heian, stressed that its highest spiritual ideals were realised through strict self-discipline.

Incarnation of Buddhist Faith

Around the mid-11th century, the Buddhist faith underwent a new incarnation. The decline of Buddhist law and the onset of a dark decadent age termed the ‘Mappo’ led people believing that the world was coming to an end. Many turned to the Amida Buddha of the Pure Land, who was thought to be a saviour. The Amida’s paradise was supposedly the west where the moon – representing Buddhist law, truth and nirvana – also sets.

Seeking eternal salvation, monk Saigyo asked: ‘My mind I send with the moon, That goes beyond the mountain, But what of this body left behind in darkness?’ At the same time, a fin-de-siècle quality permeated the transition from the late Heian to the early Kamakura era. Samurai replaced court nobles at the reins of power, ushering in a brave new age. Its possible repercussions had Saigyo saying: ‘My love will end in hopelessness, These longing sighs, I bring on myself, Are empty as the cicada’s shell’.

Although a tenet of Buddhist monkhood was the renunciation of all worldly desires and attachments, monk Saigyo continued to be moved by all around him. His poetry reveals an unresolved personal conflict between the Buddhist ideal and his love of beauty and nature: ‘Even a person free of passion would be moved to sadness, Autumn evening in a marsh where snipes fly upwards’.

Itinerant Poet-Monk Lived in Solitude for Long Periods

The itinerant poet-monk lived in solitude for long periods. Mount Yoshino was one of his favourite places in Nara prefecture, where a small hut, believed to be his refuge, has been named Saigyo-an ‘The sound of water is my companion, In this lonely hut in lulls between the storms on the peak’. Today Mount Yoshino remains covered with cherry blossoms in spring just as monk Saigyo witnessed in his time: ‘On Mount Yoshino my path strays from last year’s landmarks, Onward to flowers I have yet to see’. Occasionally he moved south to Mount Koya, and also west to the Ise peninsula and then journeyed northwards.

Saigyo died in Hirokawa Temple in Osaka prefecture at the age of 72. Most monks would choose to die facing west, where they might be welcomed by the descending Amida Buddha. Saigyo however found the Buddha in flowers: ‘I pray that I may die beneath flowers in spring, In the month of the Buddha under a full moon’.

If they exist, Heian figural depictions of Saigyo on paper would be extremely rare. A revival of narrative painting in native taste surfaced during the Edo period (1615-1858) as e-makimono, horizontal handscrolls, viewed in segments when unfurled from right to left. Offering a panorama is the Saigyo Monogatari Emaki, Illustrated Tales of Saigyo, dated 1630, the only extant work by the master Tawaraya Sotatsu (d.1643) and an Important Cultural Property.

It contains colourful episodes of Saigyo’s wanderings; an autumn scene with prancing deer in the Musashino region, and at the Nachi waterfall near sacred Mount Koya where he trained as a monk. In a special gesture, the Sannomaru Shozo-kan, the Imperial Household Agency’s museum is lending a rare supporting scroll from the Imperial family’s private collection. Like the other paintings on view, this particular scroll by Ogata Korin (1658-1716) of the Rimpa school, who studied and copied Sotatsu’s work, adds a valuable dimension to the monk, depicting him as he was seen and portrayed by succeeding generations.

BY YVONNE TAN