We live in times when culture matters, it seems, more than ever. Civilisations come and go, but what remains is their art, architecture and literature – their heritage. As a far-sighted and increasingly influential award for today’s art, design and now – architecture, the Jameel Prize is encouraging creativity that celebrates the heritage of our times, counterbalancing news of conflicts with other stories, tales that draw on art’s universal themes of beauty, exploration and transformation.

Every two years since 2009, the Jameel Prize is awarded for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition, encouraging artists to explore how long-established practices of Islamic art, craft, design and architecture can powerfully inform contemporary expressions. In doing so, the prize promotes dialogue about the role of Islamic culture in an era of sweeping change both in historically Islamic regions and beyond.

The fifth Jameel Prize was recently awarded in London at the V&A in London, and like its precedents, is a partnership between Art Jameel and the V&A. From its inception in 2009, it attracts huge international attention, as each of the editions tours to selected global venues as diverse as San Antonio to Singapore, Moscow to Morocco. Most recently, the Jameel Prize 4 exhibition visited Korea and Kazakhstan. Originating at the Pera Museum, Istanbul, and on tour in 2017 and 2018, this particular exhibition has been seen by 128,512 visitors.

The Jameel Prize is certainly worth winning – £25,000, equal to the influential Turner Prize for contemporary art. The value of the award is of course not just its financial aspect, but also due to the way it was set up and subsequently run. And because of its two-year international touring agenda, the prize ensures global exposure and prestige that translate into further opportunities for creative commissions, exhibitions and recognition for the artists.

Also, as Fady Jameel, President of Art Jameel, says of the goal of the Jameel Prize: ‘It is to widen public appreciation of the role played by Islam’s great cultural heritage as a source for our own times’. He adds that the rich and varied traditions are shared by hundreds of millions of people across a huge area, from Africa to Indonesia, and for many more in the Islamic Diaspora. The inclusive original and ongoing premise of the Jameel Prize is that candidates do not need to be from the Islamic world, nor have a personal connection with the Islamic faith.

In an era when artists are concerned with being labelled, for example as ‘contemporary Islamic artists’, curators and commentators as well have reservations about such terms. Venetia Porter, Curator of Islamic & Contemporary Middle East at the British Museum, who pioneered the collection of contemporary art of this genre for the museum, collaborated from early on with Tim Stanley to initiate the Jameel Prize, and was also a judge for short-listing works and awarding prizes. Tim Stanley is senior curator for the V&A’s Middle Eastern Collection, who was responsible for developing the award and for curating all five editions. Porter says: ‘As scholars of Islamic arts, we clearly understood the complexities of this term “Islam’’ and were often troubled by it in contemporary contexts. Should one, could one talk about a “contemporary Islamic art?” This dilemma became even clearer when the criteria for selection began to be formulated. Some artists are from Islamic countries but are not Muslim. For the first prize, we had a Jain, an Armenian jeweller from Istanbul and an Orthodox artist from Lebanon’. Stanley says, ‘It would be strange to call it “contemporary Islamic art”. It is contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition’. ‘In the end,’ Porter suggests: ‘The prescription for Prize entries calls for a clear link with traditional practices of Islamic art and craft, referring to objects, ceramics, carpets, metalwork, glass, woodwork, as well as architecture, created from the 7th to the 19th centuries in countries that were at any time under predominantly Muslim rule’.

This year includes, for the first time, an architect, Marina Tabassum from Dhaka, Bangladesh, where she lives and works. Again for the first time, the Prize was split, between Tabassum and Iraqi Mehdi Moutashar. The joint Jameel Prize 5 winners are both in dialogue with contemporary global discourses on art and have produced exemplary work in two very different disciplines. They show an awareness of modernist practices of the 20th century, which have in turn drawn on traditions from around the world. At the same time, though, they are passionately rooted in and deeply learned about their own cultural legacies.

Out of eight finalists, five were women. One of them, joint prize-winner and architect Marina Tabassum, was born in 1969 in Dhaka, graduating with a BArch from Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology in 1994. She is the Principle of Marina Tabassum Architects (MTA), a company which aims to establish a global language of architecture yet rooted to its place, prioritising climate, materials, site, culture and local history. Prior to establishing MTA in 2005, Tabassum founded URBANA with Kashef Chowdhury. Together they designed the Independence Monument of Bangladesh and the Museum of Independence in 1997. In essence her practice is global yet rooted in its locality.

Tabassum’s Jameel Prize-winning entry is the Bait ur Rouf mosque in Dhaka, built in 2012 in a densely inhabited part of the city. Its functions answer the needs of the local community, built of local materials and using indigenous yet appropriate modern building techniques, while observing Bangladeshi climatic conditions. Its design draws on medieval Islamic architecture, particularly inspired by the mosques built in Bengal in the Sultanate period (13th to 16th centuries), yet this historical reference is given a thoroughly contemporary expression. The mosque is transcendental in its play with geometry and abstraction, light and air, as well as water. So it is both a contemplative as well as an animated space. The prayer hall is essentially a pavilion on eight columns, contained by walls of porous brick. Light streams in through skylights above, permitting the space to be illumined during daylight hours, and inspiring an enhanced sense of contemplation.

Joint prize-winner Mehdi Moutashar was born in Illa, Iraq in 1943, but left in the late 1960s settling in Paris. He still lives and works in France, in Arles. Arriving in Paris, he became heavily influenced by minimalist forms, particularly the geometric abstract art of the era. His current work reflects these influences, developing them, and integrating them with Islamic traditions of sophisticated geometry and Arabic script, creating a powerful personal visual language that has wit, depth, and a pungent urgency. The judges agreed that he should be considered among the greatest living exponents of a constructivist aesthetic.

Arabic calligraphy is a redolent influence in Moutashar’s work, amply demonstrated by four examples at the V&A. Two folds at 120 degrees (2012) is made of two metal plates, which as the work’s name implies, are both folded at 120 degrees. It was inspired by an Arabic calligraphic style named riqa’, and in particular by the angle at which a scribe holds his qalam, his reed-pen, to write riqa’. Two other works are based on similar inspiration and abstraction. A fold at 180 degrees and a square (2014) and A square and three right angles (2016), are based on similar abstract concepts and calligraphic derivation. In Two squares, one of them framed (2017), the lower framed square crosses the line between the wall and the floor, that meeting point between two surfaces echoing the base line used in writing Arabic calligraphy.

Other finalists for the Jameel Prize 5 included Youness Rahmoun, from Morocco, whose practice is diverse, including installations incorporating new technologies and multimedia. It references patterns, geometry and numbers found in Islamic art, and has a particularly significant reference to Sufi mysticism. Rahmoun showed Taqiya Nor (Hat-Light), an installation of 77 hats in coloured wool, which he found in the shop of a craftsman in his hometown of Tetouan. They are connected by electric wires and illuminated by light bulbs hidden inside. The number 77 relates to the 77 secondary branches of the Islamic faith (10 being the main ones).

Jordanian Nermeen Abudail, who is a graphic designer, and architect Nisreen, who are sisters, form Naqsh Collective. Their sculptural works draw on the embroidery traditions and motifs of the Levant, and their walnut wood presentation Shawl is inspired by a real one whose specific embroidery is Palestinian; its worn condition relating to the tribulations of the country. The pattern is laser-cut into the wood, then painted, followed by the insertion of tiny pieces of brass, and finally burnished to suggest the smoothness of a woman’s shawl.

Wardha Shabbir from Pakistan was trained in the Indian miniature painting tradition, but develops it into thoroughly contemporary imagery focusing on the concept of the Islamic garden, with its cultivated elements, conveying symbolic meaning that shows concern for the path we take in life. Her composition is of two diptychs, one called A Wall, in which she implies boundaries that we construct around ourselves and necessitate breaking through. Dragonflies fly around the garden, symbolising the people and situations we encounter in life. The other diptych named Raasta translates as ‘pathway’ in Urdu. Again it is symbolic of the journey to self-awareness and search for a connection with the divine.

Born in Iran, Kamrooz Aram works in a variety of media that include painting, collage, drawing and installations, as well as architectural materials such as brass, wood and terrazzo. In an attempt to challenge contemporary Western interpretations of art history, including those covering the Islamic world, he explores how exhibition design shapes our understanding of art works. And so, in an iconoclastic way, he hones in on this concept by creating works that focus as much on the formal qualities of design and display as on the artefacts themselves. One of his contributions to Jameel Prize 5 is an installation titled Ephesian Fog (2016); others, like Ancient Through Modern 26’ and ‘28 of collages, actually include postcards of objects in the V&A’s own collections, presenting the art of the past in a Modernist context.

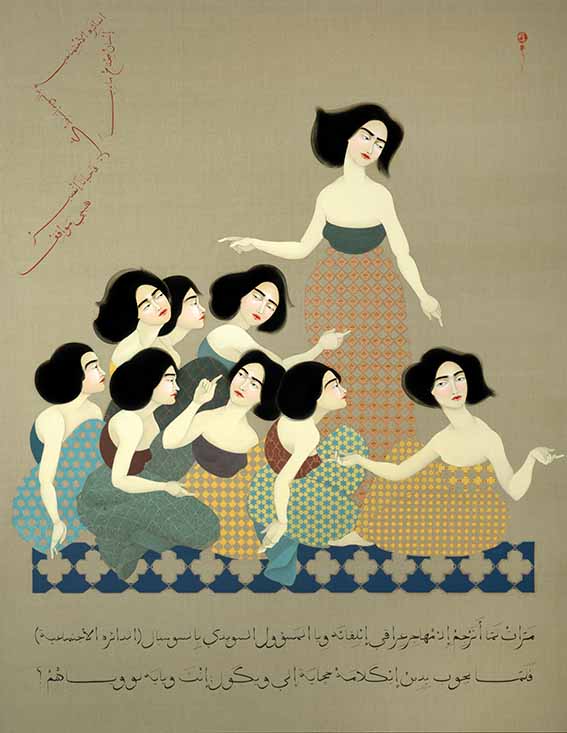

With her paintings Iraqi Hayv Kahraman explores migration, the dynamics experienced by people from the Middle East living in diaspora, as well as gender-based issues in large-scale, figurative works. At Jameel Prize 5 she shows The Translator from her series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), inspired by the illustrations in 13th- century Arabic manuscripts. With this series she aims to create a forgotten history from the perspective of an immigrant, specifically her mother, who was a translator between refugees and aid workers in Sweden. A second work, House in Gaylani, from her series Let the Guest be the Master (2014), was prompted by the sale of her childhood home in Baghdad. Her composition emphasises gender roles – the women remaining in the house, the men meeting in the courtyard.

An exciting young fashion designer, Hala Kaiksow from Bahrain, launched her eponymous womenswear label in 2016. Sustainability is the name of her game, including weaving the textiles herself on a manual loom, along with Bahraini artisans. On display are two looks including Wandress Shepherd’s Coat (2015), made from wool and denim, a modified form of an Iranian shepherd’s coat from the turn of the 20th century, which has a cartridge pleating detail that was inspired by a Cypriot shepherd’s water-bag, as well as Islamic geometry. She treats her designs like sculptures that move around the bodies that wear them. Another exhibit, Momohiki Jumpsuit, is derived from 19th century Japanese farmers’ trousers, which Kaiksow has adapted so that they can be worn by women.

So what is the legacy of the Jameel Prize? Mahnaz Fancy in Canvas magazine writes: ‘By providing a much-needed contextual dimension and bridge between the Islamic craft heritage and contemporary practice, it actually complements the rapid development of contemporary art from the region.’ The names of artists selected from previous editions read like a roll-call of those currently celebrated in today’s art world. Primarily due to its touring aspect, the Prize suddenly gives emerging and mid-career artists an international audience. Fancy mentions the Islamic craft heritage, so much of which is disappearing in areas of conflict, lack of tourism and inexpensively manufactured alternatives. By working in media such as carpets, metalwork and inlaid marquetry, today’s artists give work to traditional craftspeople, encouraging the survival of those skills.

Around 300,512 people have already seen the preceding four exhibitions around the world. But the most thought-provoking impact is the one that can’t really be analysed – how attitudes are changed. The impact created is a constantly evolving phenomenon, just as the entries to the prize are constantly changing in emphasis and media. For instance, an example of how audience perceptions can evolve is the insistence of openness of the prize to submissions of art and design, addressing those who do not consider design on a par with ‘fine art’. The prize is open to architectural submissions, which like product design interact with craftsmanship, as do calligraphy and graphic design. Art married fashion winning the 2013 prize when the Turkish fashion label Dice Kayek drew on Ottoman sartorial style. Such design considerations and creative production contribute to cultural and economic development in the artists’ countries of origin.

While the reports of Arab terrorism continue to sadden and appal us, the Jameel Prize does tell another tale. ‘It stands as a testament to artists and designers who, in a myriad of subtle ways, encourage us to look at the world from another angle’ says Venetia Porter. ‘A place where politics take second place to human aspiration and creativity’.

JULIET HIGHET

- Jameel Prize 5 runs until 25 November at the V&A, London, vam.ac.uk